Multi-proofs

Taiko supports multi-proofs through a mixture of zkVMs, TEE, and guardian proofs. Check out our blog post on zkVMs here and a Twitter thread on our Raiko architecture here.

Proving Taiko blocks

The purpose of proving blocks is to give certainty to bridges about the execution that happened in the rollup. To rely on some state that happened inside of the rollup, a bridge will want a proof that everything was done correctly. On Taiko you can run a node as a prover and prove blocks, permissionlessly. This means that you can examine the proposed blocks on the TaikoL1 contract, and generate proofs for them. Currently, any prover can create proofs for proposed blocks. This means that the number of “state transitions” has no upper bound, because we don’t know what is the correct state transition yet. Only first prover with a valid proof of the correct state transition will receive the reward of ETH (and possibly any ERC20 or even NFTs if the Prover pool implementation favors it).

Verified blocks and parallel proving

There are three states that a block can be in on Taiko:

- Proposed

- Proved

- Verified

We already know what a proposed block is (must pass at least the block-level intrinsic validity tests to be accepted by the TaikoL1 contract). Next, a proposed block can be valid or invalid, depending on whether it passes the transaction list intrinsic validity test. A block is invalid if it fails the transaction list intrinsic validity test, and this block is not created on Taiko.

Now, a block can be proved, but also further “verified”. What’s the difference? A block is proved if it has a valid proof which proves a state transition from one state (parent block) to another (current block). However, blocks are proven in parallel by the decentralized provers. So while a block can prove a parent block transitions to the current block, we don’t know if the parent block itself has been proven. As you can see, for a block to be “verified”, it needs to prove the valid state transition to the current block, but the parent also needs to be verified. We assume that the genesis block (which has no parent), is verified. So all the children blocks from genesis to the current block need to have proofs of their state transition for the current block to be “verified”.

A recent change in our protocol means we verify blocks in batches. Previously, so long as a block was verified it’s verifiedTransitionId in block data would be non-zero; now that we verify in batches, only the last block in a batch will have a non-zero verifiedTransitionId.

i.e. It is now possible for a block to be verified, and have verifiedTransitionId == 0.

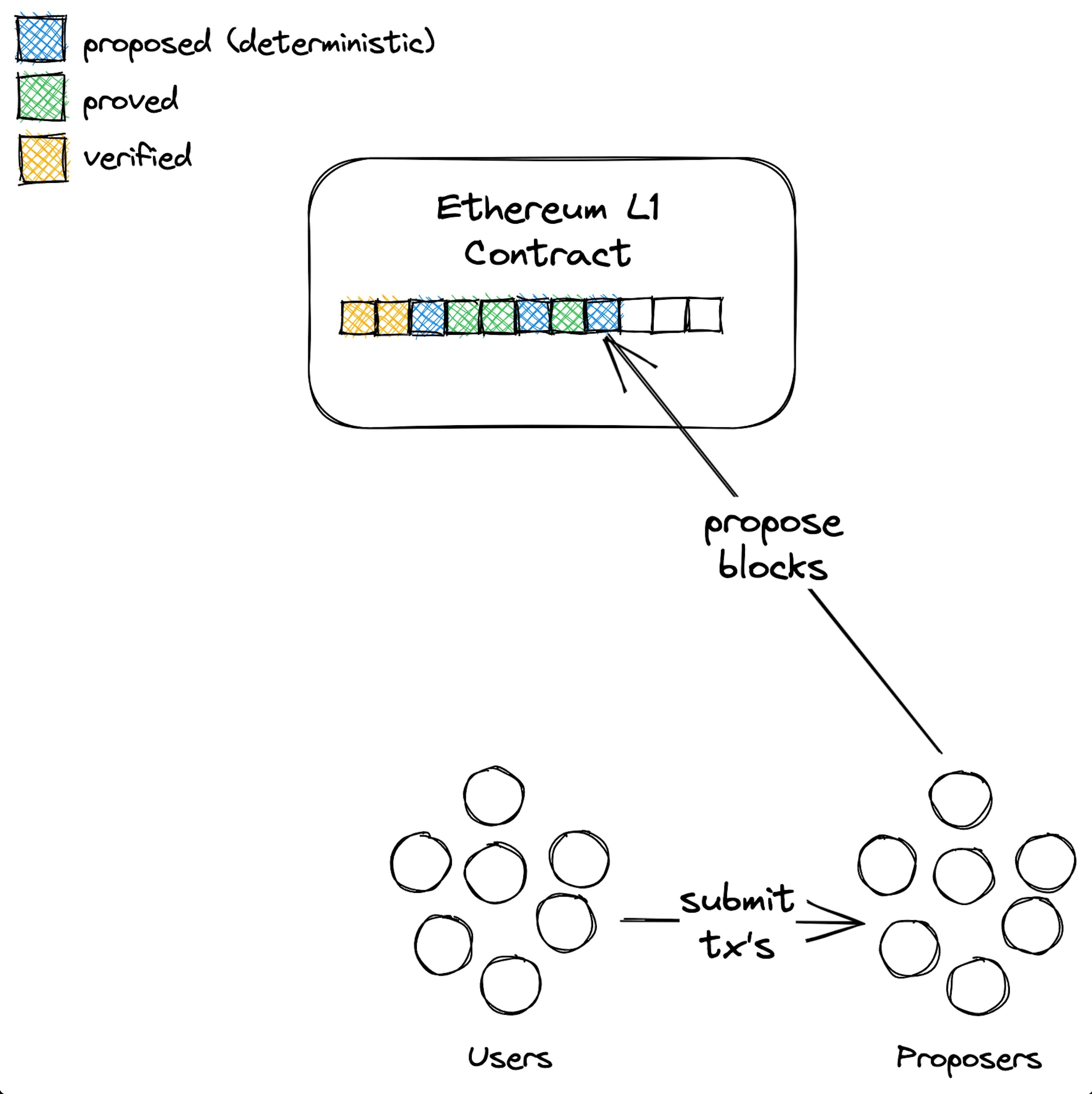

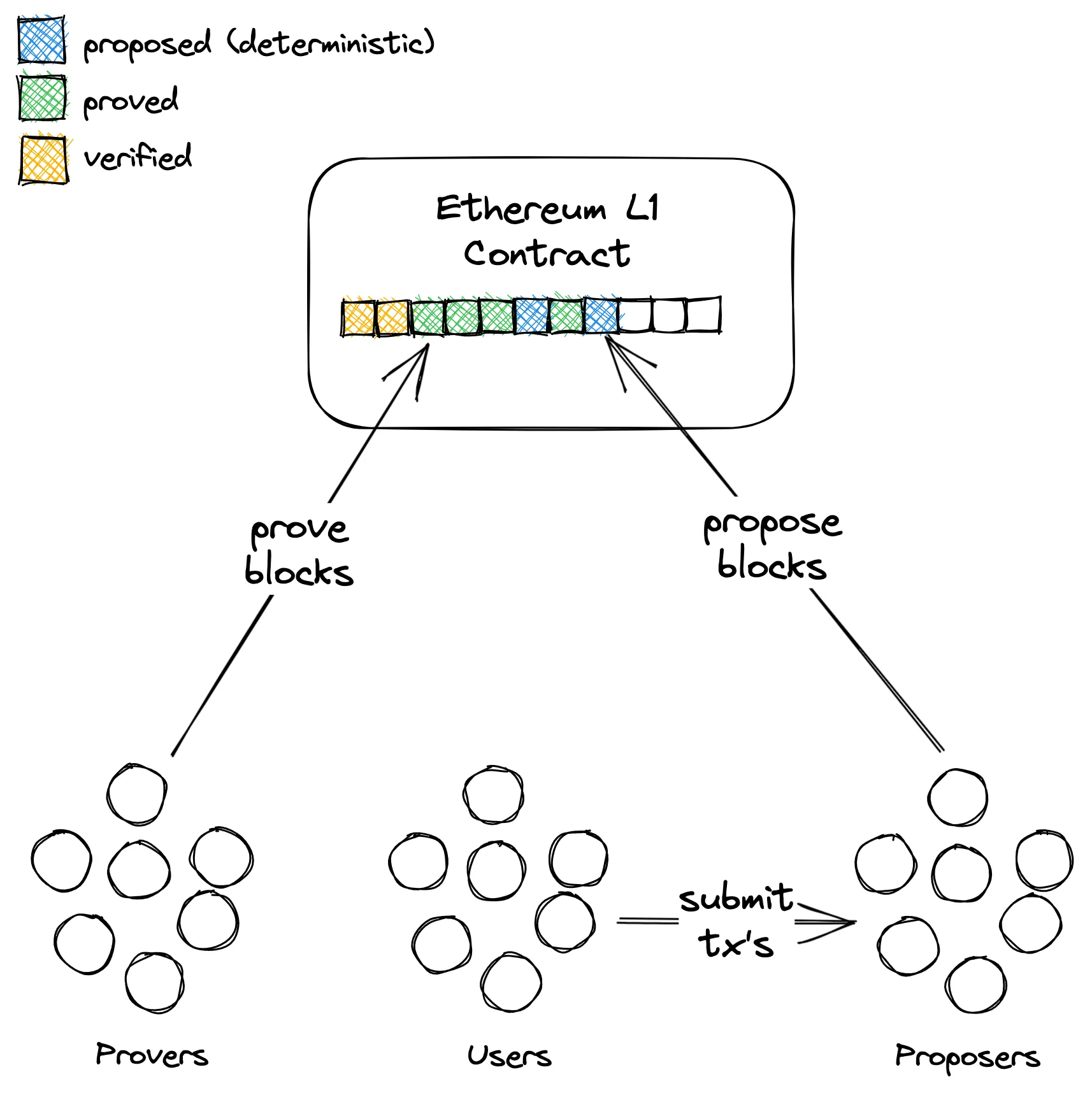

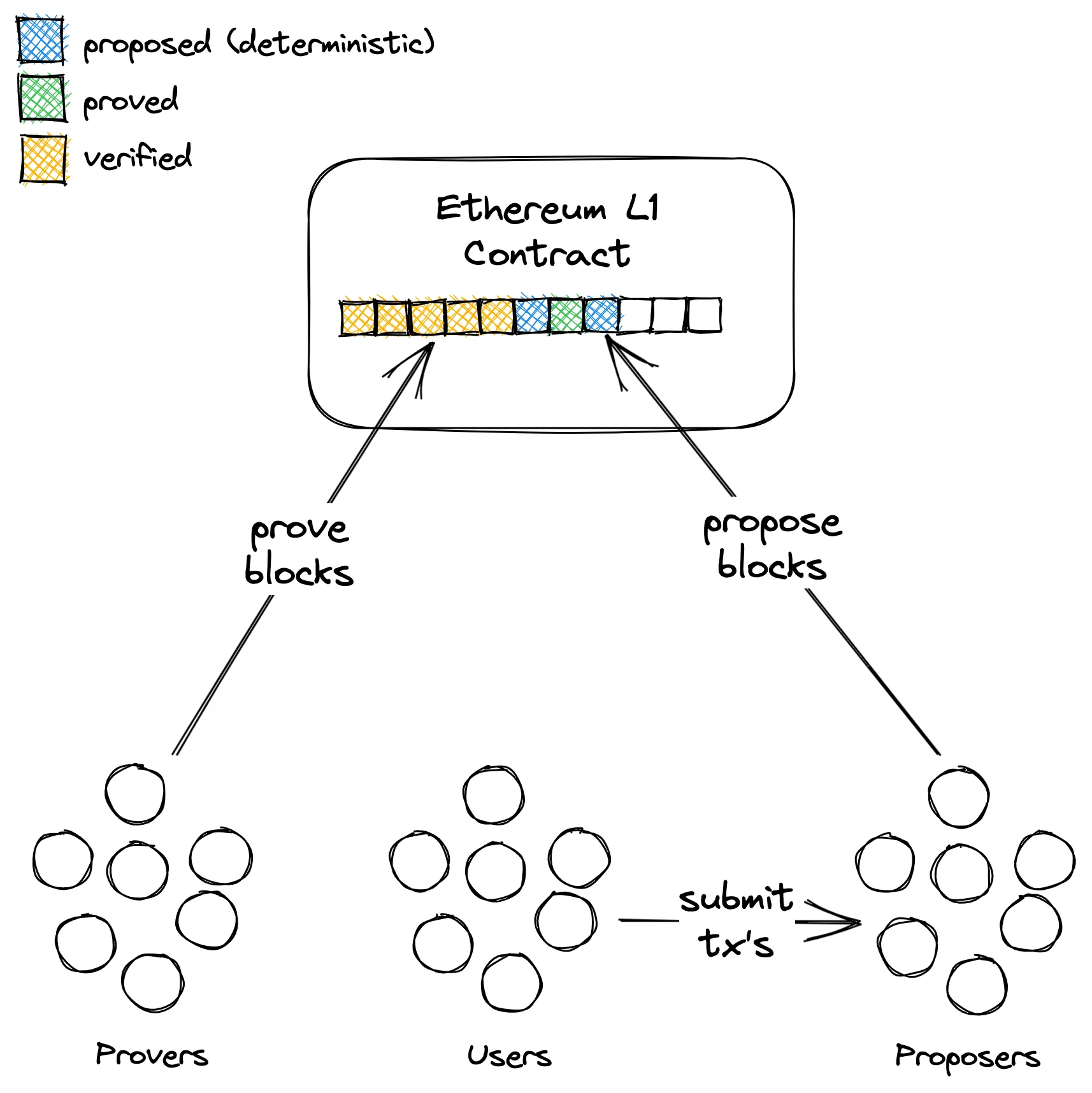

For the visual learners here is a visualization of the three stages (proposed -> proved -> verified)

Proposed:

Proved:

Verified:

Off chain prover market (PBS style)

Proving blocks requires significant compute power to calculate the proof to submit and verify the proof on Ethereum. Provers need to be compensated for this work as the network needs to attract provers that are willing to do this work. How much to pay for a proof is not obvious however:

- The Ethereum gas cost to publish/verify a proof on Ethereum is unpredictable.

- The proof generation cost does not necessarily match perfectly with the gas cost.

- The proof generation cost keeps changing as proving software is optimized and the hardware used gets faster and cheaper.

- The proof generation cost depends on how fast a proof needs to be generated.

In the pursuit of optimizing network efficiency and balancing costs, the ecosystem introduces a robust off-chain proof market. Proposers, on a per-block basis, actively seek potential proof service providers through this dynamic marketplace. A pivotal component of this setup is the publicly exposed API, providing proposers with the means to query and engage with available proof providers off-chain.

When an agreement is reached concerning the proving fee for a specific block, the chosen proof service provider is then tasked with granting a cryptographic signature to the proposer. This signature serves as a binding commitment, signifying the prover’s dedication to delivering the proof within the agreed-upon timeframe.

Provers within this off-chain proof market come in two primary forms: Externally Owned Accounts (EOA) and contracts, often referred to as Prover pools. To qualify as a Prover pool, a contract must adhere to specific criteria, implementing either the IProver interface, as previously defined by Taiko, or the IERC1271 (isValidSignature) interface.

Upon a proposer’s submission of a block, the signature granted by the chosen provider is subjected to verification. Any deviations result in a reverted transaction.

As an additional incentive for proposers, the system incorporates the issuance of TAIKO tokens. This serves as an extra motivator, as proposing blocks alone may not always prove profitable, especially when considering Ethereum’s on-chain fees plus the proving fee. The issuance of TAIKO tokens operates on a dynamic ‘emission rate per second,’ comparing each block proposal to the last.

The reward depends on the proof service provider and the agreement. For EOAs and Prover pools that implement the IERC1271 interface, the reward is disbursed in ETH. However, in cases where providers implement the IProver interface, the prover fee can be ETH, any other ERC20 tokens, or even NFTs, based on the negotiated terms.

To add a layer of security and commitment to the process, provers must provide a substantial amount of TAIKO tokens per block, effectively serving as insurance. In the unfortunate event of a failure to deliver the proof within the given time, a portion, specifically 1/4, is directed to the actual prover, while the remaining 3/4 are permanently burnt. Conversely, successful and timely proof delivery ensures the return of these tokens to the Prover.

Multi-proofs

A great resource to learn about Taiko’s approach to security with multi-proofs is the Twitter thread here.

Cryptographic implementations are complex and not yet mature. To minimize potential bugs and vulnerabilities, diversity in proof systems is needed. Taiko is one of the advocates who strongly defends the multi-proofs approach in rollups. Taiko’s approach aims to increase security and diversity by using multiple proof systems and clients, thus reducing the risk associated with bugs or vulnerabilities in any single system. The approach also includes the integration of different types of proofs.

Taiko proposes a robust multi-proof pipeline which translates assembly-level instructions coming from different execution clients into arithmetizations for algebraic or polynomial proof systems. Different backends to encode these arithmetizations, such as SuperNova, Halo2, and eSTARK can also be used, without being limited by using a single protocol.

In addition to ZK proofs, Taiko utilizes SGX (a Trusted Execution Environment developed by Intel) to generate a different type of proof. SGX runs the same code that would be executed on a zkVM, which functions somewhat like a light execution client. Therefore, all proof systems verify the same underlying light client’s execution, potentially allowing for the reuse of necessary data. The necessary data is signed within SGX using a standard ECDSA signature, employing a private key exclusive to SGX. The signature is then verified within the smart contract.